Article by Richard D. Lewis

Aspects of Truth

For many who do business overseas it’s a familiar scenario. After weeks – sometimes months – of negotiations you finally get the contract signed. Only a few weeks later, you find that the other side has reneged on the terms or now wants to re-negotiate.

So, when is a contract a contract? When a decision has been entered into the minutes of a meeting; when the ink is dry; or perhaps, when an arrangement is working to the satisfaction of both sides? As many have discovered, what is understood by a contract in one country, e.g. a mutual, binding agreement, is not always taken as such elsewhere.

Contract is Final

The Swiss, Germans, British, North Americans and Finns are among those who regard a written contract as something which, if not holy, is certainly final. When they put their names to an agreement they will, in most cases, honour it – the good name of the company is at stake. The same principle applies at the national level: British and French adherence to long-standing commitments in transnational projects such as Airbus is taken for granted.

The French tend to be precise, often extremely finicky, in the drawing-up of contracts, and, having got what they wanted, can usually be relied upon to follow through.

Latin Flexibility

Other Latins, however, require more flexibility. The Italians or Argentinians see the contract as an ideal scheme in the best of all worlds, which sets out the prices, delivery dates, standards of quality and expected gain. But the world, as we all know, is not perfect. Things may, and probably will, go wrong.

South Americans and Spaniards may sometimes fail to meet deadlines and deliver late. They will, by way of insurance, have spent considerable time and energy building up a good relationship with their trading partner and will expect understanding if they run into difficulties in meeting the contract. They may also pay late; in this the French join them.

Konepaja, a Finnish machine tool firm, discovered the hard way how Brazilians look at the terms of a contract. Their training partner always paid one year late in spite of having signed 90-day clauses. The Finns, unable to apply any moral pressure and unwilling to sue a regular customer, opted for the course of building a one-year wait for payment into their calculations. Everyone was happy with the contract.

Asian Intent

For the Chinese and most Asians, on the other hand, the contract is often considered as a statement of intent. They will adhere to it as best they can but will rarely feel bound by it – particularly if they feel cheated or legally trapped, if anything in it contradicts common sense or if market conditions suddenly change; new tax laws, currency devaluations and drastic political changes can all, in their eyes, render a previous accord completely meaningless.

The Japanese, meanwhile, see the ‘real’ contract as the one made orally in good faith during a meeting where they trusted the other side, were too polite to offend and, in all probability, understood less than two thirds of what was being said. Equally, they expect the written contract to reflect the harmonious style of the discussion. If the small print turns out to be rather nasty, they will ignore it or even contravene it without any qualms of conscience.

In the 1980s, Kanefo, a large Japanese textile company, sold 1 million white shirts, unwanted in Japan to the Chinese Government’s Purchasing Agency for a figure around $3 per shirt. The shirts subsequently proved unsaleable at the price fixed by the Japanese for their own public. They went back to Kanefo to renegotiate the buying price, which eventually came down to below $1, whereupon the Chinese bought 4 million shirts.

Correlation with Attitude to Truth?

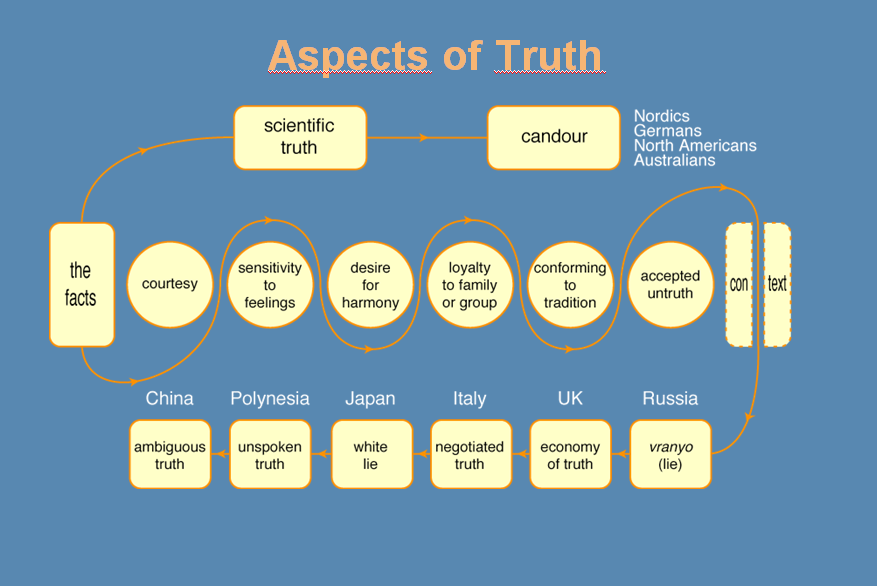

I am often asked on cross-cultural seminars whether the different attitudes towards contracts that exist around the world are a result of different attitudes towards the concept of ‘truth’. Certainly, among some nationalities, there does seem to be quite a strong correlation between the belief that truth should always be presented openly, never concealed, and the belief that contracts should be binding. In this camp are, for example, the Nordic nations, Swiss, Germans and North Americans.

Many Asian and Latin cultures allow their attitude towards truth to be affected by other concerns. Courtesy, desire for harmony, loyalty to family, can all lead to businessmen and women being somewhat economical with the details of a contract.

There is, however, one prominent exception to this correlation which is, perhaps not surprisingly, the British. As mentioned above, they do attach a lot of importance to contracts, but they do not always stick rigidly to the truth. The British are famous for their diplomacy; they often sacrifice truth in order to avoid direct confrontation.

Understandably, contrasting approaches to contracts have led to frequent disputes between Japanese and American firms. The Americans are well known for their love of detailed written agreements, which guard against all contingencies with legal redress. The Japanese who have far fewer registered lawyers compared to the US, regard contingencies to be force majeure. In such circumstances they will press for the contract to be sensibly reworked and modified at another, doubtless harmonious, meeting.

As long as you know in advance who you are dealing with and what their attitude to contracts is, you should be able to factor into your business dealings the possibility that some obligations may change in the future.

Contact us now for a free consultation and find out more about your organisation’s and your business partner’s cultural orientation and how you could improve your relations!

Post Tags: Tags: asian intent, aspects of truth, attitude to truth, contracts, latin flexibility