Case Study by Richard D. Lewis

In May 1998, when the impending merger of Daimler-Benz and Chrysler was announced, it heralded the biggest cross-border industrial merger ever. The rationale was obvious. Chrysler was perennially third in the Detroit Big Three and despite heroic efforts by Lee Iacocca to revitalize the company it struggled to maintain its productivity and world ranking. Daimler-Benz – more prestigious and dynamic – was essentially a specialist producer of premium saloons and had made few efforts to widen its product range and customer base.

The amalgamation of the two companies produced an industrial giant with global sales of more than $150 billion, making it fifth among the world’s car manufacturers. It was to be a shining example of what globalization could achieve for an adventurous group combining two well established brand names. A smooth integration of the two famous corporations would enable the group to meet the demands of nearly all segments of the car market, and sales could be expected to increase exponentially.

The phrase “smooth integration”, was a key challenge to Daimler-Chrysler as well as the route to success.

Certain elements of the Daimler-Benz management were awake to the problems likely to arise when German and American executives and work forces were to be united at various levels of activity and responsibility: German and American mindsets and world views differ sharply. There are worse cross-cultural mismatches, but there are also better ones. Wisely, Daimler-Benz appointed a senior executive, Andreas Renschler, to supervise the integration. He had worked several years in the United States and was sufficiently well-versed in both cultures to foresee and hopefully circumvent cultural difficulties which would undoubtedly present themselves.

We had worked with Mercedes executives and teams in the years between 1975 and 1995. Andreas Renschler contacted Richard Lewis Communications and arranged an initial meeting in Stuttgart to discuss training programmes for executives who would be involved in the early stages of cross-border activity. We sent a 3-man team to the headquarters in Sindelfingen – two of our English consultants who had lived in Germany and one German-American who flew in from New York. We spent the whole day with Renschler, an experienced and mature individual with a good grasp of cross-cultural issues and a keen insight into American and German behavioural patterns. We were joined during the day with a German HR team, assembled specially to facilitate the merger.

Communication styles

We made a presentation predicting the likely obstacles in the way of quick understanding. In the early stages of the merger, differences in communication styles would be the first major hurdles to be surmounted. In Germany the primary purpose of speech is to give and receive information. Americans are also factual, but use speech emphatically to give opinions and are more persuasive than Germans. In this respect they often use hype, which Germans instinctively react against. Americans tend to evince optimism and put forward best scenarios. Germans are more comfortable with a cautious, somewhat pessimistic view which envisages worst scenarios. They want a lot of context before approaching any important decision. The let’s get-on-with-it approach of the Americans often increases German caution. “Yes, but what happens if …””? is a typically German attitude. Americans are anxious to expound the grand strategy and mop up the details later. They seek simplification of issues to clarify their route to action. Germans have a tendency to complicate discussion (life is not simple, you know)

German formality is evident in their style of communication. When meeting strangers, they usually enter a room with a serious look on their face, contrasting with the broad Hollywood smiles of the Americans. Germans at this stage may seem stiff and distant to Americans. Surnames are used for years and full titles are expected. Americans go for first names from the start and have an informal way of conducting a discussion, using slang, irony and kidding, which disconcerts most Germans, especially senior ones. Germans are used to asking serious questions to which they expect serious answers. Americans, fond of humour, often reply in a rather flippant or casual manner. Germans fail to appreciate jokes, wisecracks or sarcasm during a business discussion. Germans are not fond of small talk and often find Americans chatty. Charismatic Americans find Germans lacking in charisma and perhaps dull. Germans in fact distrust charisma and instant smiles. As they generally think in silence they are not quite sure how to react when Americans think aloud. Are they making statements, suggestions, or are they trying to make their own mind up? Brainstorming is popular with Americans but less so with Germans, who would be reluctant to speak out in front of a superior. German ideas are expressed guardedly with considerable caution. American speech is quick, mobile, opportunistic. Germans seldom argue with a colleague’s remarks. Americans prefer a free-for-all discussion. Their speech is loaded with clichés (Let’s get this show on the road”. “I can’t fly this by the seat of my pants”.) or tough talk (“I tell you I can walk away from this deal”.) Both are absent from German speech. American agreements are usually reached by persistent persuasion in open discussion; Germans find agreement through thorough analysis of details, leading to clarification and justification.

Listening habits, too, are part of the communication process. How would Germans and Americans listen to each other? The American (audience) demands initial entertainment and tends to listen in snatches if not amused. The next phase is “What’s new?” Time is money so get on with it. Don’t complicate issues – tell it like it is! Slogans and catch phrases are readily absorbed by Americans. Germans don’t use them.

The German listener does not yet wish to know about the present; the past must come first. Consequently all the context leading up to the deal must be gone into. When this need has been satisfied, then one can describe the present situation, before edging cautiously forward. Questions in the mind of the German listener are “Does this sound too simple?” “What happens if …?” “Am I getting the hard sell?” “Aren’t we rushing into things?” “Can I have more (technical) information, please?”

Other differences

Diversity in communication styles would lead to early misunderstandings, but later procedural and structural differences would raise their heads. US corporations usually have strictly centralized reporting. Large German companies often feature decentralisation and compartmentalisation. Each department reports vertically to its department head. Horizontal communication across departments at different levels is practically taboo. Departmental rivalry is much more acute than in the US. In this area German managers tend to be extremely touchy. Americans are more thick-skinned. Americans go from office to office in their gregarious manner. German offices are strongholds of privacy, usually with doors shut. American managers chase their staff around the building exchanging views (“Say, Jack I’ve just had a great idea”). Germans by contrast like to do the job on their own. (No monitoring, please, until the end of the day). American managers like to shower good executives with praise (“You’re doing a heckuva job!”) German staff expect no praise from the boss. They are paid to do the job efficiently.

Germans are class conscious. Senior managers are usually intellectuals. In classless America intellectuals are often called “egg-heads”. American managers speak out loud. Senior Germans command in a low voice. Americans prize spontaneity, flexibility and adaptability in reaching their goals. Germans give pride of place to well-tested procedures and processes. If these structures have brought the company so far, why change things?

Renschler and the Mercedes training officers concurred with the points made in our presentation. What should be done in terms of training to facilitate the merger? Our basic reply was that many mergers fail because both sides are not sufficiently versed in the historical values, core beliefs, communication patterns, behavioural habits and world view of the other. Training would address these issues systematically according to the model we would put forward. An important target in such training is to make one side like the other. This transcends simple knowledge of the other culture.

It was agreed that we would refine our training model to fit the proposed merger of the two companies and would return to Stuttgart one month later with a detailed programme.

The Training Model

When we returned the following month, Renschler had assembled a somewhat larger HR team (6 or 7 people) including one professor from “DaimlerChrysler University”.

They had formed various executive teams who would tackle various projects in the merger. In Stuttgart the teams consisted largely of Germans with a sprinkling of Americans and British. Other teams, with more American members, were being formed in Detroit.

Our model envisaged a 6-month training period where teams would be exposed to full-day seminars, workshops, special briefings and a home study programme. We have formalized cross-cultural studies under the following sub-headings:

Culture: general

Religion

Cultural classification

Languages

Values and core beliefs

Cultural black holes

Concept of Space

Concept of Time

Self-image

Culture: communication

Communication patterns and use of language

Listening habits

Audience expectations

Body language and non-verbal communication

Culture: interaction

Concept of status

The position of women

Leadership style

Language of management

Motivation factors

General behaviour at meetings

Negotiating characteristics

Contracts and commitments

Manners and Taboos

How to empathize with them

Renschler and his “committee” were sufficiently pleased with the programme. It was agreed that 50-60 per cent of the activity would be carried out in Stuttgart with the aim of familiarizing the largely German teams with American mindsets and business culture, and similar “mirror” seminars would be held in Detroit to help Americans understand Germans. The emphasis throughout would be the fostering of a favourable view of the foreign partner.

As we all agreed on general principles we discussed a starting date with Renschler. In view of the urgency of the consummation of the merger, he was anxious to start as soon as possible. There was only one obstacle – the programme would first have to be approved by DaimlerChrysler University. The professor on our committee promised to submit the programme to the University the following week. Soon after Renschler changed jobs. We never heard from DaimlerChrysler again.

Five years later

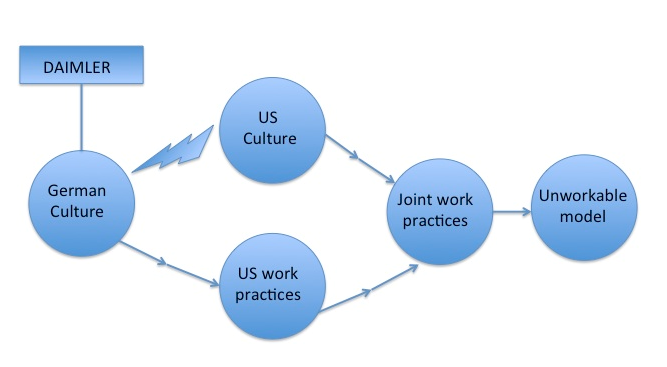

Five years later, after addressing the annual conference of the G100 group in New York, I attended a cocktail party hosted by Jack Welch and Raymond Gilmartin. At this function I met a German DaimlerChrysler board member who had been one of the first Germans to be sent to the United States where he had worked from 1998 – 2003. He gave me an account of the unfolding of events after the merger was consummated. The time taken by the DaimlerChrysler University in considering the content of a cross cultural training programme resulted in most executive teams being sent from Stuttgart to the United States with no training at all. The cultural clashes we had forecast in 1998 took place in the first few months of joint operations. Differing behavioural habits and attitudes irritated both sides; this situation was exacerbated by the maintenance of the fiction that the amalgamation was a merger of equals. It was nothing of the sort. Daimler could not afford a merger formula, with a jointly-owned company based in the Netherlands, since this would have triggered a huge tax charge. This meant that Chrysler had to become part of a German Aktiengesellschaft. It was in fact a quiet takeover, in compensation of which the Chrysler shareholders were paid a 28% premium over the then market price. Managers maintained the “merger” fiction for some time; this was relatively harmless in itself except that American staff continued to believe that there would be “joint control”. It took years to achieve any measure of integration of two different ways of working. Neither side had been given time or training to study the other’s mindset.

It is true that the Germans learnt to be less formal and to cut down on paper work; the Americans, for their part, learnt more discipline in their meetings and decision-making. German and American commonalities such as work ethic, bluntness, lack of tact, a linear approach to tasks and time, punctuality, following agendas, results-orientation and emphasis on competitive prices and reliable delivery dates created a potential modus operandi, but two different mindsets led to irritation and misunderstanding on both sides. The German board member listed dozens of incidents. He opined that the Americans he was working with showed a complete lack of understanding of German values, methods and working culture. They found that Germans shook hands too much, were often too intense and followed rigid manuals and rule books which deflated American spontaneity. German meetings were boring, American meetings were exciting; the German drive towards conformity clashed with American invention, innovation and opportunism. Germans adhered to old traditions and well-tried procedures; Americans preferred a DIY ambience. Germans who stayed on sought deep friendships, not segmented ones like the Americans (tennis friend, bridge friend, drinking friend, etc.). Americans got annoyed by the German habit of offering constructive criticism. Half the time Germans and Americans just talked past each other. Germans took long holidays, unthinkable in American eyes, especially when there was a crisis, but when difficulties arose, who was in control? For one year the group had 2 chairmen, Mr Schrempp from Daimler and Bob Eaton, who had been boss of Chrysler. Within one year Eaton was fired and his American successor lasted less than 12 months. DaimlerChrysler’s share price fell from $108 in January 1999 to $38 in November 2000. Nobody was quite sure how the combined companies should be run. Cultural differences led to divisions of opinion and methods at all levels. In German eyes, Chrysler was a company with problems in every department, not least productivity. Each vehicle took Chrysler 40 hours to make. Honda and Toyota produce a car every 20 hours. The Germans, with their emphasis on quality found Chrysler quality control way out of line. Even worse there was no plan in place to improve it. Chrysler swung from a profit of $2.5 billion in the first half of the merger year to a loss of $2 billion in the second.

The German solution was to import a crack German executive – Dieter Zetsche – to apply German principles to the problem. He set a target of 30 hours per vehicle in 2007; he slashed spending from$42 billion (five year plan) to $28 billion; he brought new models forward 6 months faster; he shut 6 factories and cut 45,000 jobs – one third of the total.

Under Zetsche’s efficient control, Chrysler was in 2006 perhaps the healthiest car company in Detroit. However a second important factor emerged from the troublesome acquisition of the American company. An initial mistake of the Germans had been that, in order not to be seen as heavy-handed, they had “stayed away” from Detroit. For this reason it took them 2 years to get to grips with the American company’s fragility. Then when Zetsche concentrated all out on rescuing his ailing colleague, Mercedes itself slipped badly. Neglect led to its reputation for quality being dented by unfavourable consumer reports and the company’s move down-market into Smart cars piled up huge losses.

Ironically Zetsche himself was moved back to Germany to assume control of the whole group. It was then the turn of the German end of the DaimlerChrysler group to undergo painful restructuring similar to that which had taken place in the previous 4-5 years in Detroit. Zetsche joked that since a Chrysler boss (himself) was now running the show in Stuttgart, everyone could at last see clearly that it was a takeover.

The case study originally appeared in the book “Fish Can’ See Water” by Richard D. Lewis and Kai Hammerich. For more information on the book or our cross-cultural services, please contact us.

Post Tags: Tags: case study, Chrysler, Daimler, merge, organisational culture